Sitting in prison in Jerusalem in 1961, Adolf Eichmann got hold of a book which he hoped would get him off the hook. The man who was to be executed the following year for coordinating the Holocaust was lucky to get his hands on a copy of this new paperback, seeing as the West German government had tried to suppress it.

Apart from an introduction and some explanatory captions, the book was little more than a collection of legal files, photographs, and newspaper clippings from the archives of the Third Reich. But all the documents related to one man, Hans Globke, who in 1961 was one of the most important civil servants in the West German government, state secretary and senior advisor to Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.

Entitled “Dr. Hans Globke – File Extracts and Documents,” the book showed that Globke had helped draft some of Germany’s anti-Semitic laws in the early 1930s – even before Adolf Hitler’s accession to power – and had later been one of Eichmann’s most important officials, with a brief that spread across several departments in Hitler’s government. Now the book was a last straw for Eichmann to clutch at, and with its help he wrote 30 pages for his defense attorney, detailing his relations with Globke and attempting to prove that the civil servant had more authority than he ever did. He failed, but the book had struck several nerves, provoking defensive statements from Adenauer and, supposedly, threats against the publisher from the German intelligence agency the BND.

Careers continued

Its author was Reinhard Strecker, a fierce archiver and campaigner whose work caused many sweaty palms among top West German officials in the 1950s and 1960s. For as he wrote in the introduction, “Globke is no unique case.” In spring 1960, Strecker filed charges against 49 former judges who had actively participated in the Nazi regime and continued serving in West Germany. In the same year he displayed his research in an exhibition – 105 ring-binders of laboriously photographed files laid out in the back room of a student bar in Karlsruhe. “It was completely improvised – but it was totally packed out,” remembers Strecker. And its impact was seismic.

The exhibition, called Ungesühnte Nazijustiz (“Unpunished Nazi Judiciary”), grew and toured a number of universities across the country, causing rows between students and faculties, and attracting national and international media. The exhibition was tailored to each city in which it was displayed, highlighting local state prosecutors and judges. (“After all, there was someone with a past everywhere,” Strecker once said.)

Strecker, who often found himself locked out of German archives, got help first from Warsaw, which gave him full access to Polish state archives, and then from Britain, where a handful of MPs invited him to speak to an all-party committee in the British parliament. He also travelled to Jerusalem to be one of the few non-Jewish historical and legal experts invited by the Knesset to help prepare cases against Nazi war criminals.

In addition to causing much embarrassment to the Adenauer administration, and not a few quiet early retirements of judges and state attorneys, Strecker’s work ultimately fed into the intergenerational tension that was gathering pace in Germany in the 1960s, which would culminate in the 1968 student movement.

International upbringing

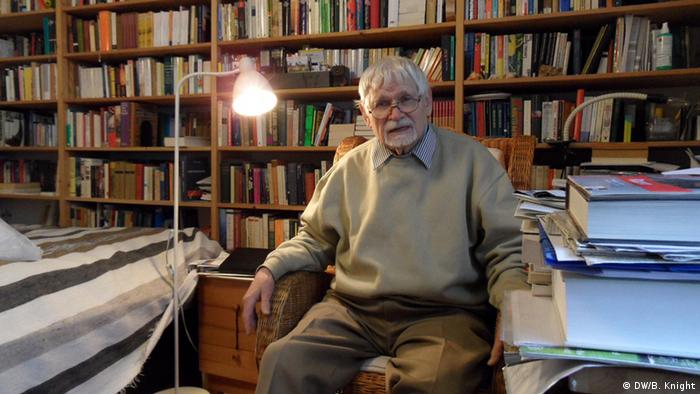

Now aged 84, Strecker lives a quiet life in the Friedenau district of Berlin. His study is lined on one side with books – including many classics of British and American literature – and on the other with what remains of a vast store of courtroom files from the Third Reich.

His parents were decidedly anti-Hitler. “Unlike I’d say 90 percent of lawyers at the time, my father was never a member of the party,” he says. “That had to do with the fact that for my parents, church and religion still meant something.” As earnest Christians, Strecker’s parents were politically active in the doomed struggle to keep the Protestant Church free of Nazi organizations, and did all they could to keep the young Strecker out of the Hitler Youth, which was mandatory.

When the war in Germany ended, Strecker aimed to get out of the country as soon as he could. (“School didn’t seem important at the time.”) At 16 he hitchhiked first to Italy and then headed for London – “English was always the language of liberation for me.” But he only made it as far as Paris, where he spent several years at school. Despite being the only German in the class, he says he never faced mistrust from his French fellow students. “They just thought of me as one of the leftovers,” he said. He also met and was deeply affected by the Spanish republicans who had fought fascists in the Spanish civil war.

These travels gave Strecker a new, outsider’s perspective when he returned to Germany in 1954 – and found it wasn’t a country that had changed as much as he would have liked. “I had a very bad impression of Germany when I came back,” he says. “I didn’t like any of the personnel at all – the Adenauer-Globke system. Adenauer had just one aim – he wanted to restore Germany’s reputation in the world. That took up all his time. He wanted to prevent any Nazi crimes from facing German courts. And he largely succeeded.”

Under Adenauer’s chancellorship, it was left to individual German states, rather than federal authorities, to investigate Nazi crimes. On top of this, a memo has been discovered from 1963, when Germany and Israel were negotiating new diplomatic relations, in which Adenauer asked Israel to stop pursuing former Nazis. “This is intolerable for the reputation of Germany in the world,” the chancellor wrote.

After the Nuremberg trials (1945-49), which were set up by the Allies, no Nazi crimes went to trial in Germany until Frankfurt in the 1960s, by which time Adenauer’s tenure had ended.

Postwar whistleblowers

Strecker was not the first whistleblower – his most important predecessor was a wounded veteran, Eckart Heinze, who was put to work as a courier at the German Foreign Ministry before the end of the war. “When the new ministry was created, he was very surprised about all the Nazi criminals who were still there,” recalls Strecker, who ended up working with the young officer. “There were more Nazi party members in the new Foreign Ministry than there ever were in Hitler’s time!” Under the pseudonym Michael Mansfeld, Heinze wrote a series of articles exposing the war criminals he was suddenly working for.

At the time, Strecker was catching up with his German education, studying Indo-Germanic languages at Berlin’s Free University, and gathering a handful of students to prepare his exhibition. He eventually got help from the Socialist German Student Union (SDS), an association that became a burden, since much of the West German press, along with the government, would denounce him as a communist in the pay of the Soviet Union. (“Bullshit,” is all Strecker will say to that.)

“But I never thought my work would be a success, because you couldn’t damage this concrete mafia of old Nazis in Germany,” he said. “Especially since the government successfully prevented any Nazi crime ever reaching a federal German court. Only the state judiciaries dealt with the issue, and only later.”

Now, more than 50 years after Strecker’s exhibition, and 70 years after the liberation of Auschwitz, the German judiciary may finally be attempting to correct the oversights of the past. Last year, Oskar Gröning, known as the “accountant of Auschwitz,” was arrested, and is due to stand trial this spring, aged 93. Given his age, Gröning is unlikely to serve any time even if convicted, but the ruling will have symbolic power for a judiciary that once attempted to deny its past.